Alternate title: I Hate It When Mickey Kaus Can Say “I Told You So.”

When we first met John Edwards, he was already a self-made man, if a rather one-dimensional one. He was a brilliantly successful lawyer with a lovely family but no political or civic commitments to speak of. (Prior to the 1990s it’s not clear that Edwards

voted in public elections, that’s how little engaged he was.)

Then his oldest son died in an auto accident, and that was supposed to be the conversion experience, the awakening to a broader horizon, a higher plane. Also a forging experience, a trial by fire: if a man can endure having to identify his son’s body at the morgue, he can endure anything. So John would make his mark in national politics. It was his mission, to honor Wade’s memory and strike a blow against the chaos and oblivion that Wade’s death represented.

He made it to the U.S. Senate in 1998, his first time out, hardly breaking a sweat except for injecting a few millions from his own fortune into the campaign. Truth be told, Lauch Faircloth was a lousy opponent. Faircloth would never have beaten Terry Sanford in ’92 except for Sanford’s poor health and (as Democratic pols noted closely) Sanford’s vote against the first Gulf War.

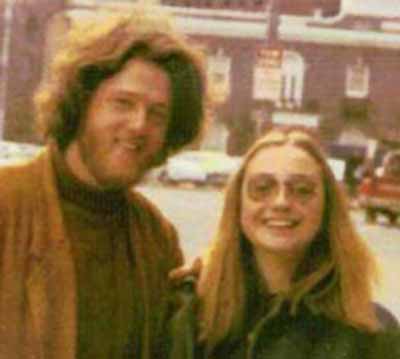

John fit the Bill Clinton profile rather well: charm and a Southern drawl combined with a progressive sensibility and obvious campaigning skills, the gifts of oratory and empathy, of “feeling their pain.” He lacked Clinton’s lifelong fervor for politics, but his talent rivaled Clinton’s; observers spoke of Edwards in similarly glowing terms. Plus he seemed to correct some of Clinton’s flaws. He certainly had the picture-perfect family life and marriage, with Elizabeth in some ways an improved version of Hillary: equally smart and less abrasive. Later, in his post-2004 makeover, Edwards would make economic populism and poverty reduction his hallmarks. He would also recant his 2002 vote to authorize Bush’s invasion of Iraq. Each of these moves seemed to respond to the most often-heard gripes from the left about the record of Bill Clinton and by this time Hillary Clinton as well.

Being a Senator was a drag for John. No slight intended—it seems to be a confining place for many talented and restless pols, especially liberals. So in the 2004 cycle he tested the presidential waters, made a decent showing, wound up as Kerry’s running mate. John got mixed reviews for his work as the VP nominee, but a bright spot (to me at least) was the performance of Elizabeth: bright, telegenic, but always a support and complement to John, never stealing the spotlight in a harmful way. (A definite contrast from Teresa Heinz Kerry.)

The Democratic ticket lost, and in the meantime Edwards had relinquished his Senate seat. So there he was in early 2005, gainfully unemployed as a Presidential Candidate in Waiting. In the midst of this pirouette came the initial diagnosis of Elizabeth Edwards’s cancer. John withdrew from public life in view of Elizabeth’s health crisis, but the assumption (or hope) was that the hiatus was temporary. Indeed, within about a year John was back in the news, and Elizabeth’s cancer had been integrated into his political bio. He was newly concerned about health care reform, newly attuned to the insecurities of American families. His second presidential bid was soon green-lighted.

In the 2008 cycle, Elizabeth was hands-down the most appealing thing John had going for him. His young family and the special partnership he and Elizabeth had were foregrounded; she was as visible a presence on the hustings as the demands of her treatment and the family would allow. Her 2007 cancer recurrence was merely a bump in the road. The couple was so forthcoming, even bold and in your face, in disclosing details of Elizabeth’s medical struggles. His supporters had a special affection for the family, and felt they had an intimate understanding of life in the Edwards household. This was all by design.

None of this stands up to the revelation of Edwards’s affair with Rielle Hunter. His reputation and political persona are in tatters. The domestic tableau, the family solidarity with Elizabeth in her cancer fight, the image of John and Elizabeth as perfectly meshed gears in both public and private life: those images are ruined. The noble mission of service to the public good, of a rendezvous with destiny, doesn’t jibe with a rendezvous with Ms. Hunter: flatterer, thrill-seeker, professional hanger-on, above all a bit of a flake. And the Bill Clinton parallels are heartbreaking for the unlearned lessons, uncorrected flaws. Besides the womanizing, there are the legalistic denials of the National Enquirer story, and the hush-money payments engineered by Edwards’s fixer Fred Baron. The last part doesn’t out-Nixon Nixon but it just might out-Clinton Clinton.

I’m not entirely sure why I come down hard on Edwards when I spent a lot of time defending Bill Clinton in Monicagate. It would be better if our politicians’ consensual sex lives didn’t impact their career trajectories, but given the Web and round-the-clock cable and tabloid journalism, it’s hard to picture a time when Francois Mitterrand standards will be in effect in the U.S. And none of our current crop of pols has really challenged the tabloid standards. Part of my disappointment with Edwards is that, more than most, he made his marriage and family part of his campaign resume`. Even Bill and Hillary weren’t joined at the hip quite like John and Elizabeth.

As Hanna Rosin puts it, you live by the confessional culture, you might die by it.

I don’t quite know what to do with the “recklessness” charge, that John E. was putting the Democratic Party in unthinkable jeopardy by pursuing the nomination with this time bomb in his back pocket. This underestimates the basic psychological defect of all presidential hopefuls, who consider themselves Men or Women of Destiny.

I sure do want to win this year, though. Many would say I failed to recognize the threat posed by G.W. Bush in 2000, but at least the U.S. was in basically sound health at that time, versus a shockingly degraded condition right now. I’m willing to compromise on principles such as candidates’ privacy, and ideals such as public campaign finance, to help the cause of Obama and the Democrats in November. And I really hate that the Edwards scandal has

revived alternate history scenarios that fuel the outrage of the Hillary dead-enders.

As usual, there are other, better writers making my points more effectively. Slate’s XX Factor blog has had some lively reflections from various angles. See also

Pastor Dan at Street Prophets on the implied covenant between leaders and followers.